License Plate Game

A fun game to play in the car.

When I was a child I’d play a game on car trips, I’d look at the license plates of nearby cars and try to do sums with them. In Ireland license plate numbers have the form Year - Place - Number, where the number is just a counter incremented for each car registered in a given place in a given year. So you end up with something like 08-D-12345, meaning the $12345^{\rm{th}}$ car registered in Dublin in the year 2008.

The game I would play was to take the number at the end, something $> 1$ and $< 100,000$, and try to make a balanced equation out of it by inserting simple mathematical operators and an $=$ between the numbers. For example $1234$ can be ‘solved’ because you can write $1 - 2 = 3 - 4$. Easy. A slightly more complicated one might be $86349 \rightarrow 8 = 6\times4\times3 / 9$. There are some that can’t be solved though, for instance $1235$.1 I think you can see where I’m going with this, can we write a piece of code that will find solutions where they exist?

First thing, given two sides of an equation we can easily check if it’s valid using Python’s eval function,

def is_valid(eqn):

lhs, rhs = eqn

return eval(f"{lhs} == {rhs}")

This takes in a tuple, two strings containing either side of the $=$ sign, and gives a True if they evaluate to the same thing. Now we just need to generate all of the possible equations given a number. To do this we split the number in all possible ways,

def splits(n):

return ((n[:i], n[i:]) for i in range(1, len(n)))

Next, for each side of the split we generate all combinations of operators,

def all_ops(eqn):

lhs, rhs = eqn

lhs_ops = combinations_with_replacement("+-*/", len(lhs)-1)

rhs_ops = combinations_with_replacement("+-*/", len(rhs)-1)

return product(lhs_ops, rhs_ops)

and then we interleave those operators between the numbers, $(+-, 123) \rightarrow 1+2-3$.2 Finally we hand those equations into the is_valid function.

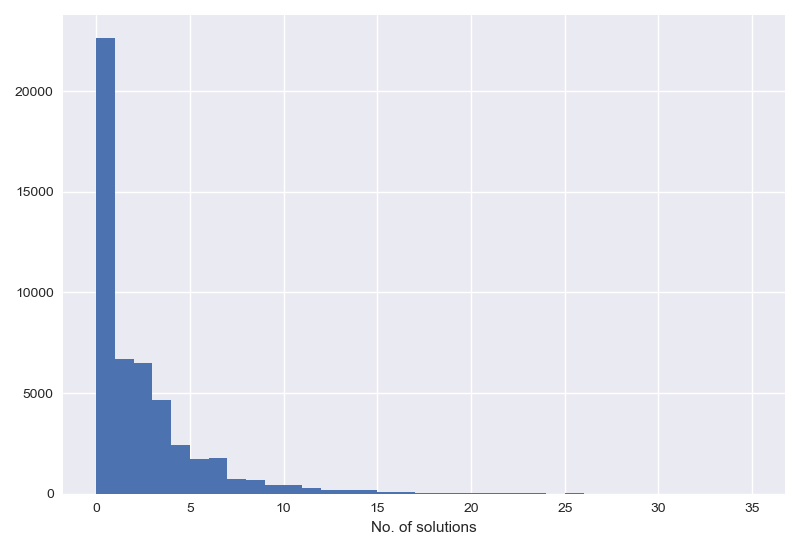

This generates a lot of equations; a 4 digit number will generate $36$ equations, a 5 digit number $120$. But the code is pretty quick, we can check all the numbers up to $50,000$ in a couple of seconds. Here’s a histogram of the number of solutions,

So lots of plates aren’t solvable ($\sim 45\%$), $13\%$ have exactly one solution and after that there’s a fall off in the number of ways you can solve an equation. The most solvable equation can be done in 25 different ways and it’s $11110$ (obvious enough, when you think about it).

To be honest I was a bit disheartened to see that only half of the equations are actually solvable, that’s a lot less than I would have thought. That said, as it stands we’re missing something fairly important, operator precedence. Currently we’re limited to the simple rules of arithmetic, we’d have a lot more flexibility if we could add parentheses to equations to change the order of operations. Another change I’d like to make is a slight alteration to the rules to make things easier.3 Instead of trying to put in an equals sign and balancing two equations, we’ll just try to get the whole equation to equal $0$. This simplifies things a bit, for instance $1137$ is not solvable under the old rules but now we can write $(1 - 1)\times3\times7 = 0$. Let’s implement these changes and see what we get.

Adding parentheses actually turns out to be a bit of a headache, you have to worry about putting them in valid places, balancing them, taking care of nested parens, etc. All told it’s very fiddly. Thankfully we don’t have to use parentheses to determine precedence, they’re solely an artifact of our infix operator notation. We can use Reverse (or Standard) Polish notation, which allows you to specify precedence unambiguously without needing parens. For example, $3 - (4 \times 5)$ is written in RPN as $3\,4\,5\times-$.4

Now our problem is that we need to be able to parse RPN equations. Thankfully this is very easy to do,

class NotValidEqnError(BaseException): pass

def rpn(string):

ops = {'+': add, '-': sub, '*': mul, '/': truediv}

stack = []

for s in string:

if s in ops:

try:

stack.append(ops[s](stack.pop(), stack.pop()))

except:

raise NotValidEqnError

else:

stack.append(float(s))

if len(stack) > 1: raise NotValidEqnError

return stack[0]

This simple bit of code is an RPN calculator, it parses strings, performs operations and gives a result. It can even do error checking for us.5 With this calculator we can adjust our function for checking validity,6

def is_valid(eqn):

try:

return rpn(eqn) == 0

except NotValidEqnError:

return False

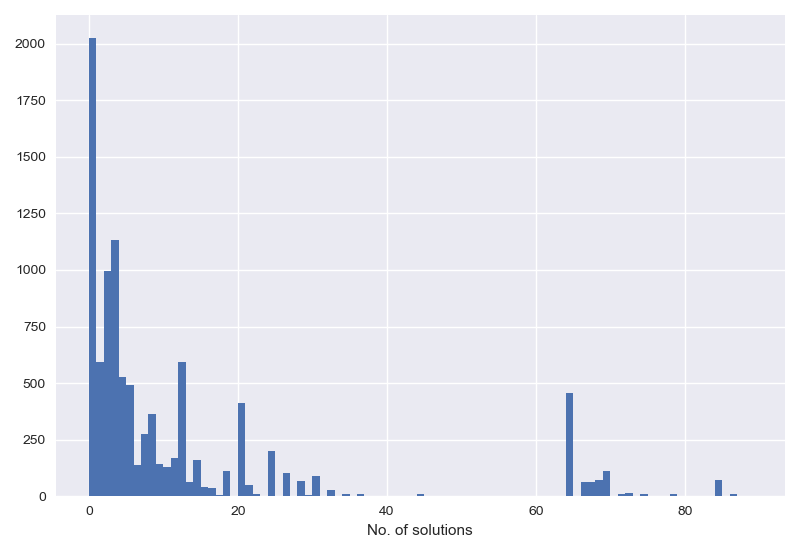

Now we need to generate all of the possible RPN equations by the same method as above – generate all operator sequences, insert them between/after the numbers – and feed them to this function one by one. There are a lot more possible equations when you use parens, and as a result the code takes a bit longer to run (and I’ve not done any optimisation). Running it on the numbers $<10,000$ we see that now only $20\%$ are unsolvable, and those that are solvable have more solutions,

This time the most solvable number is $1100$, it can be made equal to $0$ in $90$ different ways, with lots of different, equivalent, nested paren patterns.

So there you have it, armed with the knowledge that 80% of the time it is possible to win this game give it a go next time you’re in the car.

-

The first example can also be solved $12345 \rightarrow 1\times2 = 3+4-5$ ↩

-

I feel totally justified doing this, I invented the game after all. ↩

-

I’m not going to go into detail on how RPN works, Wikipedia has got all you need to know. ↩

-

What is can’t do is handle numbers $>9$ as input, but that’s fine for this use case. ↩

-

The reason we have to catch NotValidEqnError is even though all our equations will be well-formed we might do something not allowed like divide by zero. ↩