(SGD Linear Regression)

SGD, functionally.

I thought it would be interesting to put together a functional version of Stochastic Gradient Descent, as an example of the functional programming tools that are available in Python. It’s a useful little exercise, and leads to what is (in my opinion at least) a nice piece of code. This example comes from a talk I’ve given a fews times on FP in Python, the slides are here.

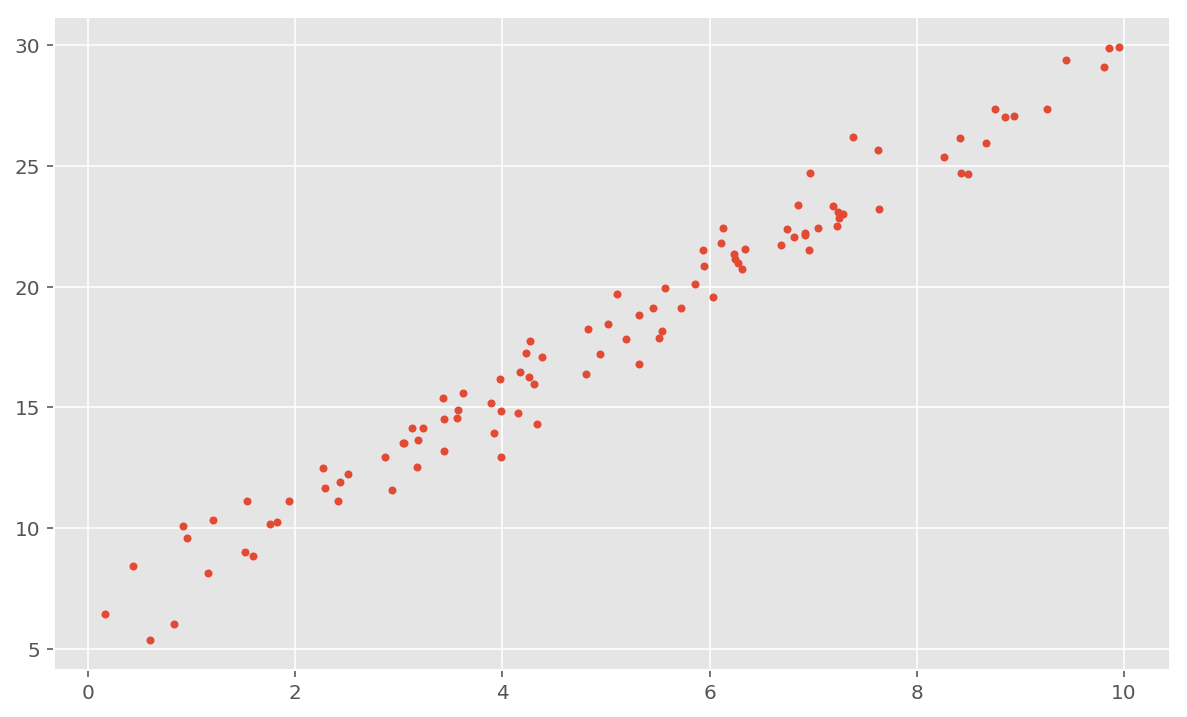

Let’s start off with some data, drawn from a linear model

Vector = List[float]

Params = Tuple[float, float]

def model(theta: Params, x: float) -> float:

m, c = theta

return m * x + c

def get_data(n: int) -> (Vector, Vector):

m, c = 2.4, 5.9

x = [rd.random() * 10 for i in range(n)]

f = lambda x: model((m, c), x) + rd.normal()

return x, list(map(f, x))

x, y = get_data(100)

plt.plot(x, y, '.')

Great. Now the concept of SGD is that we are going to fit a model to these data by,

- taking an initial guess at the parameters of the model

- computing the gradient of the error for those parameters

- moving ‘downhill’ in the direction of greatest slope to get a new set of parameters which reduce the error

In the case of a linear model like this we can get the gradient analytically,

def err(theta: Params, x: float, y: float) -> float:

return y - model(theta, x)

def grad(theta: Params, x: Vector, y:Vector) -> Params:

N = len(x)

e = [err(theta, xi, yi) for xi, yi in zip(x, y)]

c_g = sum(-2 / N * ei for ei in e)

m_g = sum(-2 / N * ei * xi for ei, xi in zip(e, x))

return [m_g, c_g]

Based on this error gradient we can write a function to take a single SGD step,

def sgd_step(x: Vector, y: Vector, theta: Params) -> Params:

lr = 0.001

m_g, c_g = grad(theta, x, y)

m, c = theta

m_ = m - lr * m_g

c_ = c - lr * c_g

return m_, c_

This function sums up the core of SGD, we compute the gradient of the error at a given point, and alter the parameters by the gradient times some small learning rate.

The thing we’d like to do now is take a series of steps, applying this function recursively until we reach convergence. And using itertools and (maybe my all time favourite Python library) toolz we can do this in a nice, clean, functional way. First thing we’ll need is a function which checks for convergence,

def until_convergence(it: Iterator[Params],

eq: Callable = lambda x: x[0] != x[1]) -> Params:

it2 = tz.drop(1, it)

pairs = zip(it, it2)

return tz.first(itertools.dropwhile(eq, pairs))[0]

This function makes use of some concepts that aren’t often leveraged in Python, and are more common to FP languages. It takes in a potentially infinite iterator,1 in our case the potentially infinite sequence of parameter updates from our SGD, and it creates a second iterator which is simply the first iterator shifted by one. Then we can zip these together, ending up with an iterator which pairs off the [(fist-second), (second-third), (third-fourth) etc.] values of the input. We then take the first value from this iterator for which our convergence criterion is met – by default we check for equality between consecutive values but this can be easily altered by handing in a different function to evaluate, i.e. is the differnce $\lt \epsilon$.2

Now that we have this convergence checking function we can simply hand this function an infinite list of SGD steps and it will tell us when to stop,

def sgd(theta: Params, x:Vector, y: Vector) -> Params:

step = tz.curry(sgd_step)(x)(y)

return until_convergence(tz.iterate(step, theta))

Here we see the power of the FP framework, the entire algorithm can be boiled down to 2 lines of code (one of which is really just book-keeping). We create a new function called step which curries the sgd_step function from above, inserting the data into the function. We then use the toolz.iterate function, which will create an infinite list from a function and a starting value,

Writing it in this way looks a little unusual, but this is allows us to do iteration without needing to write a while or for loop. This kind of recursive function application is not normally possible in Python, which puts a hard limit on how many recursive function calls are allowed, but using toolz we can get around this. We use the until_convergence function to terminate this process when 2 successive steps are equal to one another (i.e. when the gradient is 0).

I have to say I’m a big fan of doing things this way; it takes very few lines of code, we can type check all of the individual parts, and it’s extremely explicit, in the sense that we can easily see the algorithm that underlies the solution.

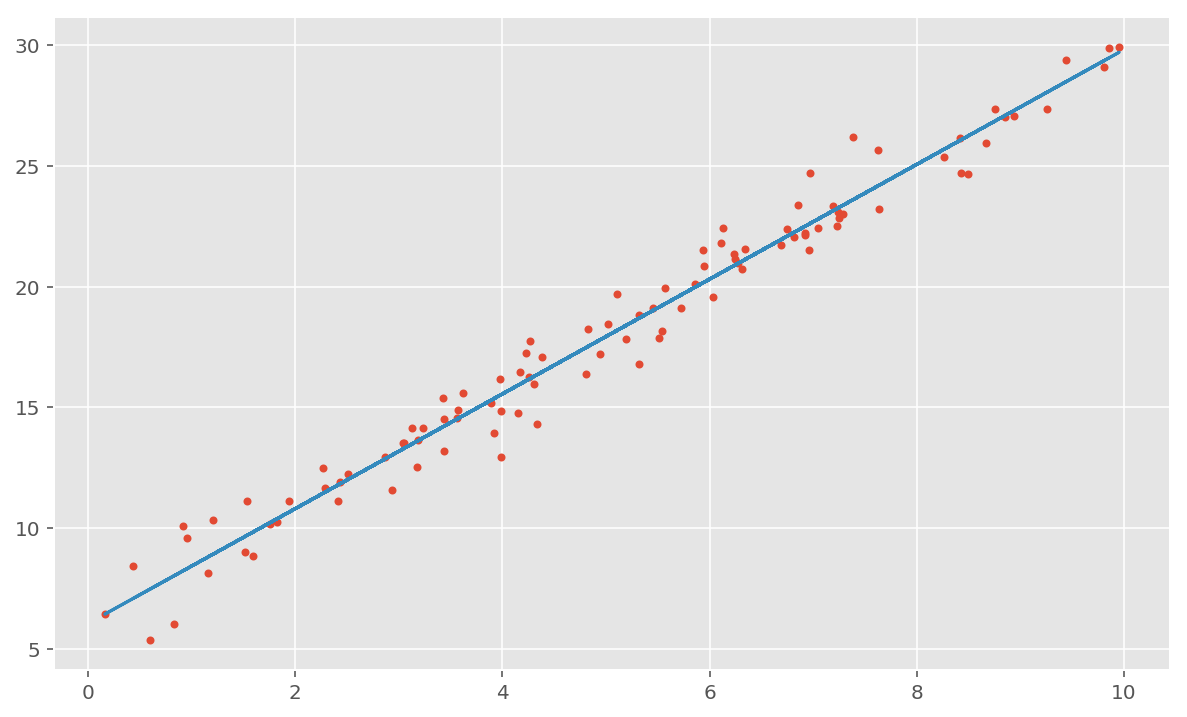

Running this code we get:

m, c = sgd((1, 1), x, y)

plt.plot(x, y, '.')

plt.plot(x, [m*xi + c for xi in x])

And there we have it. If you ever find yourself actually doing linear regression this way you should probably stop, but it’s interesting to look at if nothing else.

-

Python’s generator syntax is incredibly useful for working in a functional way, I frequently find myself working with objects like this. ↩

-

This does lead to use evaluating the error at each point twice (once for the ‘ahead’ iterator, and once for the ‘behind’ iterator), this is a pretty small expense in this situation, and could be avoided with caching (

@lru_cache) ↩